By Mike Dolan

LONDON (Reuters) – The fashionable idea that the world economy has arrived in a new more inflationary regime post-pandemic may ring hollow in Switzerland – one small vignette questioning how durably things have changed for the world’s big central banks.

A global pandemic, inflation spikes, energy shocks and rancorous geopolitics ended a decade of deflation battles and near-zero interest rates, as policymakers embarked on one of the most brutal tightening episodes in decades from 2022 to 2023.

While this is now starting to reverse, many economists assume a much-changed world characterised by de-globalisation, protectionism, energy refits and high public debt will likely result in a higher landing zone for inflation and sustainably higher interest rates than over the prior decade.

But the Swiss National Bank must have missed the memo.

In March, the SNB became the first major central bank to start easing. And this week it returned to what it considers a “neutral” policy rate of just 1%, with a promise of more cuts to come. It’s not hard see a scenario where it’s back flirting with zero – or even negative rates – within a year from now.

Far from a brave new world of high pressure pricing, Swiss inflation has subsided to just 1.1% and it’s been back in the 0-2% target range for more than a year. Strikingly, the central bank this week slashed next year’s inflation forecast to just 0.6%.

SWISS EASE

Switzerland is of course a relatively small open economy with idiosyncratic problems and a perennially overvalued currency – one historically prone to “safe haven” demand in times of geopolitical stress.

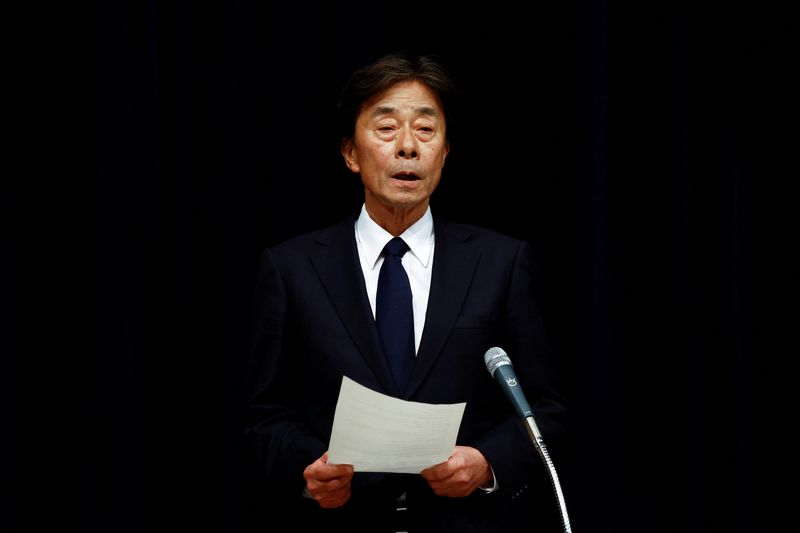

But as outgoing SNB boss Thomas Jordan and his successor Martin Schlegel pointed out again on Thursday, the strength of the franc, which touched nine-year highs against the euro last month, is a key factor squeezing prices and crimping embattled exporters.

With the currency so central to SNB policy, the prospect of running out of interest rate rope again re-introduces the prospect of a return to central bank’s own particular brand of “quantitative easing” – selling francs for other currencies.

At the height of its previous long battle to frustrate the franc’s rise, the SNB’s balance sheet of foreign currency – widely banked in assets from euro zone government debt to U.S. megacap stocks – expanded to more than 1 trillion francs ($1.1 trillion), or some 125% of Swiss GDP.

While the SNB has lopped some 200 billion francs off that balance sheet since the return on inflation and positive interest rates, it may soon find itself back in the trenches.

And if that’s not exactly “square one”, it’s awfully close.

Some banks, such as the country’s own financial behemoth UBS, think SNB easing may already be near the end of the line. They posit that its early easing was mostly sufficient, so this cycle should end after a few further cuts.

But if the European Central Bank and Federal Reserve are only just getting going with their rate cuts, risks to the franc are skewed. That’s especially true given that disinflation pressures are still mounting worldwide, with crude oil prices currently cratering at an annual rate of 25%.

Throw in numerous geopolitical risks – not least November’s U.S. general election – and it’s clear the SNB may have its work cut out for it reining in the franc.

PLUS CA CHANGE?

While you can characterise much of the SNB saga as a lonely Swiss conundrum, its pre-pandemic years of zero and negative interest rates and balance sheet expansion were widely replicated – most clearly in the euro zone and Japan.

Numerous structural and demographic headwinds were among the reasons both of those larger economies were in that boat. And it begs a question of what has changed materially since the pandemic to alter assumptions about the “steady state” of demand, prices and interest rates going forward.

The ECB’s battle with the recent inflation spike already appears to be largely over, with swaps market pricing showing it undershooting its 2% target over the next two years and dovish ECB policymakers clamouring to ratchet up the pace easing.

The Bank of Japan is coming from the other direction, only recently beginning a “normalisation” of interest rates after decades of deflation and zero or negative rates. But if price pressures wane again, the extent of that may be clipped as well.

China – finally facing up to the deep-seated problems related to its ongoing property bust and deflation scare – is now furiously easing monetary policy too and may also find itself gravitating toward a zero rate world eventually.

The United States may well be in a different place, but even senior Fed officials have recently mulled the possibility that it could undershoot its inflation target on its journey to whatever “neutral” policy may prove to be.

The more the world changes, perhaps, the more it stays the same.

The opinions expressed here are those of the author, a columnist for Reuters.

(By Mike Dolan; Editing by Jamie Freed)